Copper Mining

Copper Mining - A background to the industry

Copper Smelting Technology - From South Wales to New South Wales

Lentin's description of copper smelting in Anglesey in 1800

Ure's description of the smelting process at Swansea, in 1861

The six stage smelting process used at Cadia in 1861

South Australia - The Copper Kingdom

Kapunda

Burra

Wallaroo, Moonta and Kadina

The Bon Accord Mine, Burra, South Australia

Copper mining in New South Wales before 1860

Copper Mining - A background to the industry

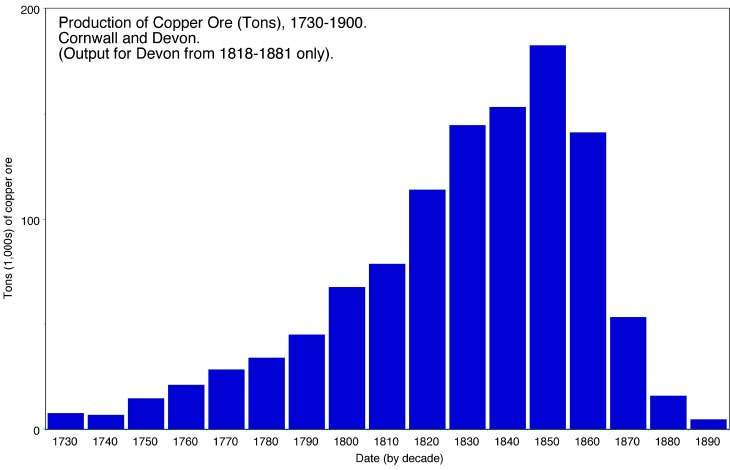

The establishment of the Australian copper mining industry principally depended upon Cornish mining expertise as well as Welsh smelting technology. This specialisation had arisen because of the location of abundant ores in Cornwall and West Devon, while the closest available supply of plentiful coal for smelting purposes was located in South Wales, in the Swansea District.

“Tin mining in Cornwall started very many centuries ago and survives today; copper mining by comparison was short-lived, being virtually unknown before 1700 and virtually extinct by 1900. Yet in these two hundred years the red metal far surpassed tin in value and tonnage, and for the century from 1750 to 1850 it is fair to say that Cornwall’s prosperity or otherwise was based first and foremost on copper…As an industry it rose and fell swiftly, and the great exodus of miners in the latter half of the nineteenth century took place as a direct result of the collapse of the great copper mines in the 1860s.

…free-trading Cuban and Chilean copper, richer by far than even the most resplendent purple and yellow ore ever raised in Gwennap, had cast its looming shadow over Cornwall by 1840, and things were never to be the same again. Another quarter of a century, and the unbelievably massive copper finds in South Australia and Michigan beat the Cornish industry to its knees and, not many years thereafter, to its death.”

(D. B. Barton. A History of Copper Mining in Cornwall and Devon. D. Bradford Barton Ltd. Truro. Second Edition. 1968: 7-8).

While tin was obtained from alluvial workings from prehistoric times in Cornwall, it was not until the 1580s that the first recorded exploitation of copper resources was reported in England.

The removal of the monopoly of the Mines Royal allowed Cornish copper mining to expand.

Under Letters Patent, dated 1564 and 1604, the Society of the Mines Royal was given the sole right to mine for gold, silver, copper and quicksilver over much of England and Wales. The first attempts at copper mining in Cornwall and smelting at Neath in South Wales in the 1580s failed. After this time the Society ignored copper in favour of lead mining. By legislation in 1689 and 1693 the “dead hand of monopoly” was abolished, opening the way for others.

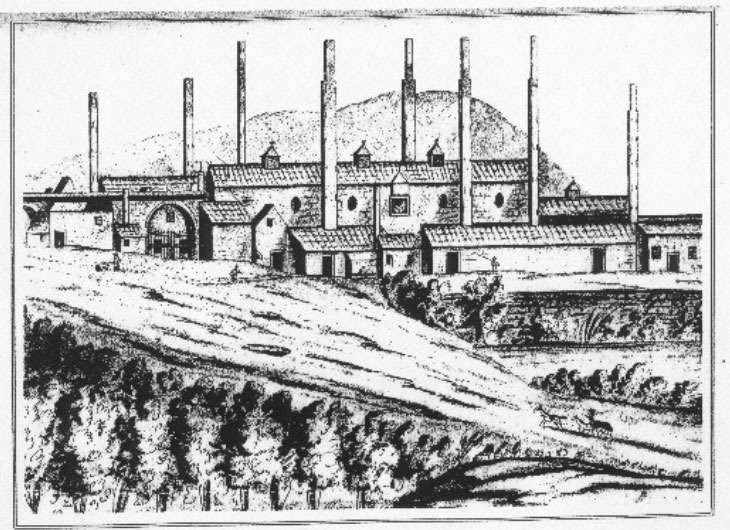

The Llangavelach Copper Works, near Swansea, 1745 (George Grant-Francis. On the Smelting of Copper in South Wales. Pritchett & Taylor, Printers, London. 1881: 106).

With the removal of monopoly, the copper smelting industry was able to develop in the 1680s, predominantly in South Wales, but also in Bristol. Major figures like John Coster, who has rightly been called the “father of Cornish copper mining”, leased copper mines in Cornwall to ensure supply of copper ores.

The demand for copper ores now stimulated the opening up and development of the incredibly rich copper resources around Camborne and Redruth in Cornwall.

By 1717 the first smelting works were constructed at Swansea, South Wales. They were within easy reach of the South Wales coalfields and a day’s sailing closer to Cornwall than Bristol or Neath. These advantages soon made Swansea the world’s centre of copper smelting for nearly 150 years. By 1800 the banks of the River Tawe at Swansea were heavily developed by various smelting works.

The East Pool Whim is one of the few engine house in Cornwall with its engine in place. It is similar to the rotative beam engine at Cadia (Edward Higginbotham, 2006).

With the increased demand for copper, the Cornish mine adventurers soon turned from tin to exploit this new resource. The richest deposits were located in a swathe from Camborne and Redruth to Gwennap. As time progressed, other deposits were exploited further east, culminating with Caradon Hill in 1836 and the huge Devon Consols (Devon Great Consolidated Copper Mining Company) in 1845. Fortunes were soon made from the richest deposits, though the Cornish miners themselves, the men, women and children, were rarely living at more than a subsistence level.

“The single parish of Gwennap at this time yielded a full third and more of the world’s entire copper output, its population having doubled in the first three decades of the century…By 1841 the parish was the most populous in the whole country, its 10,796 persons exceeding that of Truro, Camborne and Redruth” (D. B. Barton. A History of Copper Mining in Cornwall and Devon. D. Bradford Barton Ltd. Truro. Second Edition. 1968: 51).

Trends soon emerged in the development of the copper mining industry. As mines grew deeper, so the primitive pumping equipment became inadequate, demanding both improvements in drainage and pumping machinery. The adoption of explosives made mining more economic and enabled the construction of many kilometres of drainage adits and tunnels, often linking several mines together, the Great County Adit in the Gwennap area being the most extensive.

The eighteenth century became a race to develop more efficient engines to allow pumping and raising of ores from deeper levels. Cornish miners were further pushed to innovate by competition from the open cut mines of the Parys Mountain in Anglesey, North Wales, which provided a glut of copper from 1768 to the 1790s.

The development of pumping engines is associated with the names of Thomas Savery in 1698, with Thomas Newcomen and his first beam engine in 1717 and his first in Cornwall in 1720. Smeaton had nearly doubled the efficiency of the Newcomen engine by 1775, but it was the firm of Boulton and Watt at their Soho Works, whose engine with a separate condenser provided the efficiencies required to combat the threat from North Wales. The first Boulton & Watt engine was put to work at Chacewater Mine in September 1777, but the Cornish were unable to break free from this monopoly until the patent expired in 1800. By this time the Cornish engineers were ready to market their own designs.

Richard Trevithick, of Camborne (1771-1833), was the most famous of the Cornish engineers of this period. He was responsible for the adoption of high pressure steam power and the adoption of the safe, high pressure Cornish boiler. He erected his first engine at Stray Park, Dolcoath Mine in 1800, but was also responsible for innovation in small compact, high pressure engines, leading to ground breaking inventions in steam locomotion.

The advent of the Cornish engine spurred on the development of deeper mines that served the industry through its peak period of production from the 1830s to the 1850s and are a familiar part of the Cornish mining landscape. Their reliable reputation led to the technology being exported internationally. Indeed Cornish engine houses are a familiar part of the Australian copper mining landscapes of South Australia, though the one at Cadia is the sole outlier in New South Wales.

The Towanroath Pumping Engine House built in 1872 at Wheal Coates, St. Agnes, Cornwall. Cornish engine houses characterise the mining landscape of the South West of England (Edward Higginbotham, 2006).

By the 1850s the demise of the Western Cornish mines was now becoming evident, with the Caradon and Tamar areas in the east still on the ascent. Foreign competition was also becoming a threat. From a totally dominant position in the 1830s, Cornwall was surpassed in production by Chile in the 1850s. South Australia and Michigan in the United States were also beginning to have an impact by this time. The peak in Cornish and West Devon production passed in 1855-1856 and began a slow decline.

“The great days were over. Companies folded up. Mines closed down. Hundreds, then thousands, of tin and copper miners found themselves out of work, without hope of employment…there was no alternative to starvation…but mass emigration. A third of the population left Cornwall before the end of the century, while back at home their mining towns and villages were left unpeopled, the mines themselves deserted.” (Daphne du Maurier. Vanishing Cornwall, 1967: 106).

To stay meant starvation, but we should ask the question what it had in store for those who emigrated. For the Cornishmen, who came to South Australia and New South Wales, we can see some general outcomes. For a few of the Cornishmen, who lived at Cadia in New South Wales, we can follow some individual life paths.

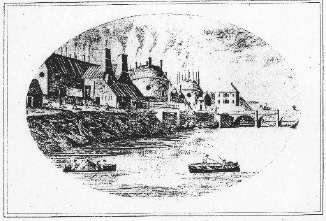

The Forest Copper Works, near Swansea (George Grant-Francis. On the Smelting of Copper in South Wales. Pritchett & Taylor, Printers, London. 1881: 149f).

One of the most interesting historical trends in the Cornish copper mining industry was the ownership and location of the smelting industry. The Cornish were always dissatisfied with the prices paid by the Welsh smeltermen for the Cornish ores. However even with the removal of duties on the coastal coal trade in 1710, smelting in Cornwall was never a viable option: it was always more economic to “ship the ore to the coalfield rather than the fuel to the orefield.”

Not only that, but the Welsh were loath to share the secrets of smelting technology. The first successful smelting operation in Cornwall was set up in 1755, the Cornish Copper Company, near Camborne, but depended on knowledge gained through family connections with the smelting industry in South Wales. Production at the Hayle Copperhouse remained small, but it also developed a sideline in the supply of timber, coal and iron to the mines, a thriving business that survived long after the smelters had closed soon after 1800.

Competition from the “Great Discovery” at Parys Mountain in Anglesey eventually forced the Cornish miners, the Welsh smelters and the Midland manufacturers to join forces in 1875 with the establishment of the Cornish Metal Company. Although a failure, other joint companies were set up from 1790 onwards, starting a trend to buy up the Welsh smelting companies. The Cornish began to buy into the Welsh smelting industry.

In 1803, Pascoe Grenfell, a Cornish adventurer, went into partnership with Owen Williams, son of Thomas Williams, the Anglesey mine owner, in founding the Copper Bank Smelting Works at Swansea.

By 1809 Richard Hussey and John Henry Vivian, son of John Vivian, had opened the larger Hafod Copper Works at Swansea. These works became the pre-eminent smelting works of the area with the Vivian family members, namely John Henry Vivian and H Hussey Vivian, considered the leading men of their day.

In 1831, the Williams of Scorrier, together with Joseph Foster, bought up the works of the Birmingham Mining and Copper Company at Swansea. Henceforward the works of Williams Foster & Co played a leading role, closely followed by Vivian & Sons.

By the 1850s, the Swansea district was smelting 90% of Britain’s production. The scene was now dominated by Vivians and Williams Foster, closely followed by Grenfell & Sons and by Sims, Willyams & Co. In other words, Cornish interests now owned the majority of the smelting capacity of South Wales, a complete reversal of the situation when the Cornish Metal Company was wound up in 1791. Some of the smelters at Cadia were related to these families.

After 1850, Chilean smelting works began to take business from Swansea and by the 1880s the vast American mines in Michigan, Montana and Arizona were in full production, again reducing the role of South Wales. The smelting industry in South Wales was extinguished by 1914.